From a very early age, there were plenty of outward signs that Ketna Patel was destined to become an artist. Growing up in an Indian family in Kenya, she was always the one who’d volunteer to paint the doorway as part of that nation’s celebration of Diwali, a festival of light. When an aunt fell sick or when Christmas rolled around, she would be the one to design the cards.

Yet in retrospect, those precocious flourishes of creativity actually had very little to do with Patel eventually becoming an artist who uses everything from bright colored paints to advertising icons to historic figures like Mao and Gandhi to create works that mix trenchant social commentary with cheery aesthetics. What really pushed Patel to become an artist—she won the ASEAN Art Award in 2002 and has had exhibits around the globe—was fear that her parents’ and grandparents’ desire for her to quickly settle down and marry a nice boy might actually come true. “I knew what I didn’t want to do, which was to be like my mom or aunt or neighbors,” she says. “I think I had a low level of panic running through me about being like everyone else.”

So Patel ran, first from Kenya to London, then later to Singapore and more recently to Wales, with extended stays on a variety of continents along the way. It has been that nomadic existence—one in which she has been a perpetual outsider and observer—that has been key to the creativity that fuels her art. “I think the word creativity is overused and has become a label embedded with connotations and clichés, but it’s about delving into the unknown,” says Patel, whose work these days focuses on bridging the divide between East and West. “I can look back now and say that flight into the unknown is a prerequisite for the creative process. The more familiar a situation becomes, whether it’s marriage or what you eat or your habits, that is the beginning of the end for creativity.”

Thinking big, thinking ahead

When Patel actually starts painting or working on a collage or a piece of furniture, she has already done an enormous amount of work. There’s lots of research about symbolism, and consideration about the mixture and size and placement of images on a canvas or a chair. Together, she says, they have to be cohesive and create a provocative narrative. “I let my brain marinate in the juices to form the story, then when I do the painting it all comes out. If you’re a surgeon, the prep is longer than the actual surgery.”

I can look back now and say that flight into the unknown is a prerequisite for the creative process.

But when Patel works, she also considers the implications of one individual piece in her larger body of work. “I prefer to work in collections,” she says. “I think when you’re an artist and you’re inviting people to an exhibition with 20 paintings that have nothing to do with one another, that would be bewildering.” Which is why Patel does so much careful preparation before she ever picks up a brush.

Mixing the everyday with high art

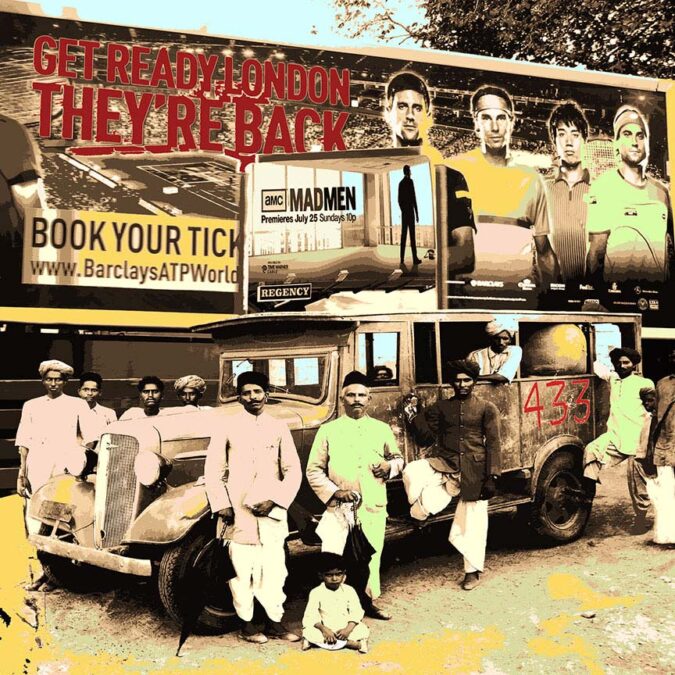

A willingness to embrace being labeled odd and a determination to avoid routine in everything from her dinner menu to where she actually lives are two essential ways Patel has nurtured the creativity that fuels her work. So, too, is her ability to mesh imagery and objects from everyday life with so-called “high art” in a way that creates work that is provocative and multilayered. “If you look at our houses and our objects and obsessions with a magnifying glass, you have a better grasp of where humanity is at than with the grand narrative at the opera or museum,” she says.

Even better is when the two co-mingle because referencing and modifying well-known classic art provides a hook and shared visual narratives to pique people’s interest. For example, Patel’s Fall of Venus uses Italian renaissance painter Sandro Botticelli’s The Birth of Venus as a familiar visual scaffold to tell a very different story. “The original painting represents a world full of beauty and creativity, and we are living in a world that is increasingly ugly and dark,” she says. In her painting, Venus is replaced by a haggard-looking Statue of Liberty with a “Clearance Sale” sign around her neck. On either side of Lady Liberty are Mao, a notorious womanizer, with two Japanese geisha girls, and Draupadi, a famous character from Indian mythology. In the background, pink smoke billows out of the stacks of an oil refinery.

I let my brain marinate in the juices to form the story, then when I do the painting it all comes out. If you’re a surgeon, the prep is longer than the actual surgery.

Obviously, the layers and meanings are many, and touch upon everything from environmental degradation to the troubled history and relations between China, Japan and India. Despite the stark messages, Fall of Venus is vibrant, mixing bright colors of the sort common in Japanese illustrations with Flash Gordon comic books. As with everything in her work, this is purposeful. “It’s a very strong graphic statement, and I wanted to take on board the power of the advertised image today and how much craft goes into that and how little goes into painting and how beautiful everything is,” she says.

Making sales personal

The advertised image is something Patel thinks a lot about. On the one hand, she points to corporate influence as a reason for diminished creativity generally—replaced instead by the sort of emphasis on efficiency and maximum productivity that breed routine. Yet she also says there is great power, even beauty, in marketing images today. “I wouldn’t throw the baby out with the bath water and say everything done in the guise of marketing is evil and sinister,” she says. “I think the worlds of fine art and marketing have porous boundaries and the trick is to weave in and out of them.”

Naturally, as someone who makes her living as an artist, Patel has to market and sell her work. And she has to do it at a time when she believes that galleries, the traditional vehicles for sales, are in decline. In part, she says, that’s due to expensive real estate in major cities requiring galleries to sell large quantities of art, a reality that impacts the quality of the work itself. “Everything has to be sellable, so there’s no risks with the work,” she says. “If you can’t take a risk, you’re pandering to mediocrity.”

Patel sees the demise of big-city galleries engendering more direct communication between artists and their audience. While much of that will take place online, Patel has personally had the most success when she has interacted with buyers personally. When she lived in Singapore, Patel had a makeshift gallery in her home. “There was something about the person coming to an authentic space that was not made up in a calculating way,” she says. “I would have to do basic things like have labels on the work and explain things and be professional. But it was the authenticity that sold the deal.”

As she navigates an art world that is changing, Patel will again be in the sort of disorienting territory that she has long used as creative inspiration. But she’s quick to add that there are no barriers to entry. “It can happen if you’re a wife or an accountant; it doesn’t belong to outwardly creative people,” she says. “You just need a heightened ability to venture into the unknown.”