Having hauled in $104 billion in revenue for 2022, the creator economy shows no signs of slowing down.

Upward of 2 million people currently label themselves as professional content creators earning a living exclusively from photography, games, writing, video and audio that they showcase or sell online. An additional 46.7 million identify as amateur content creators—with 48% having monetized their work at a rate of approximately 6 times greater than the national minimum wage. For almost half of that number, money earned from content represents half of their monthly income. In both professional and amateur categories, 40% of monetized creators are making more money from content now than they did in the two years prior.

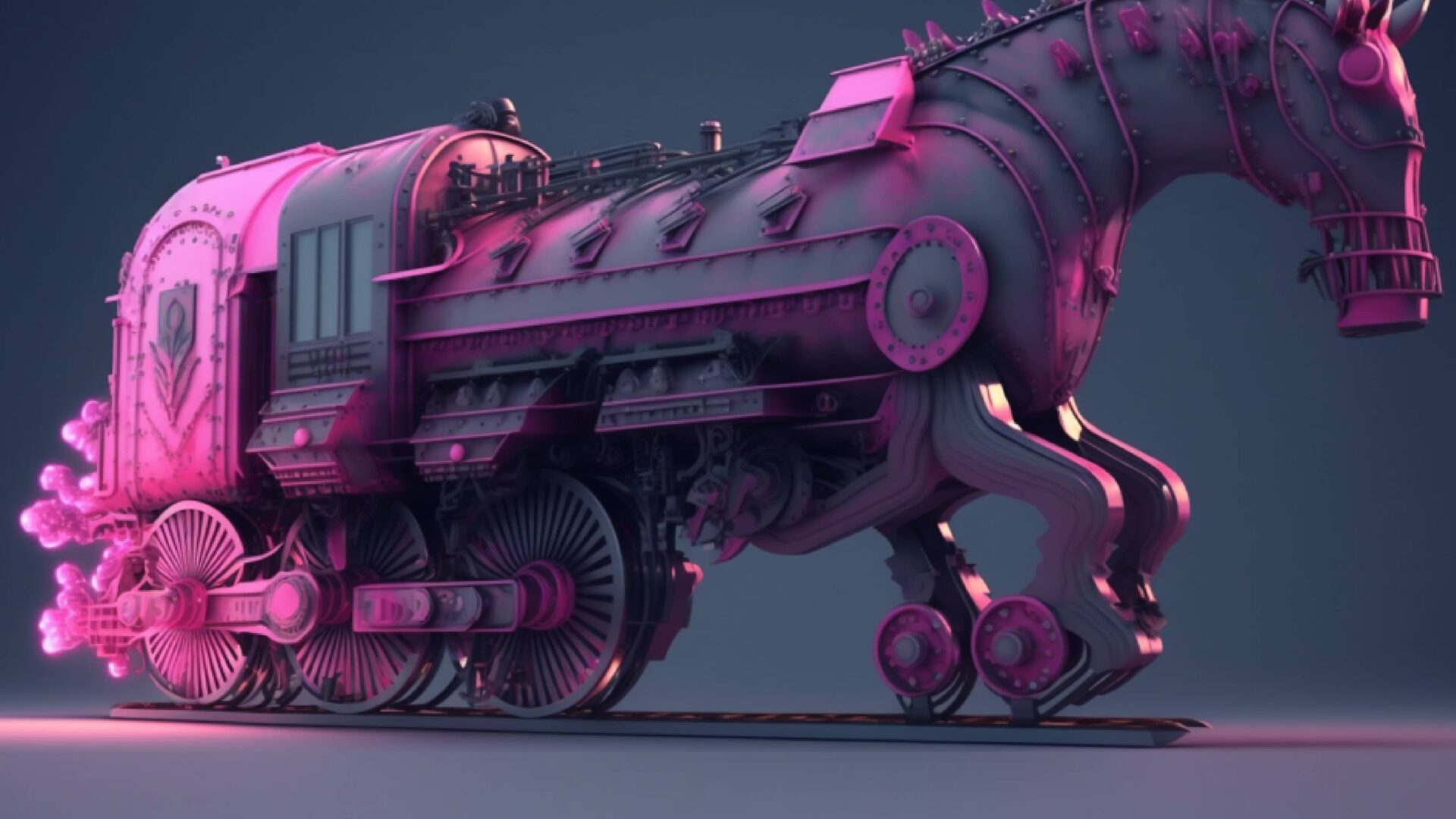

But while this still-new economy continues to gather steam, a significant portion of creators are beginning to confront an uncomfortable reality. Though the tracks for this Web2 gravy train were laid and maintained by independent creators, most of the infrastructure on which they rest is owned by someone else.

Creators are responsible for driving traffic and profits in this new economy, but the delivery of their content is mainly controlled by a handful of platforms. Big names like Instagram, TikTok, Amazon, Spotify, YouTube and Facebook have the final say on how those tracks are maintained and shifted—and on how the profits being hauled in are distributed.

Table of Contents

- Lessons of the Iron Horse

1. You can’t fix what you don’t own.

2. You’re in no position to negotiate.

3. The digital world is full of ghost towns. - Brand Central

1) Making a personal website brand central

2) Rerouting from general access to specific experiences

3) Creating a network effect

4) Treating non-ownable platforms as ad space - The End of the Line

Lessons of the Iron Horse

While the challenges faced by the small creators and big brands powering this new and lucrative sector of the economy are unique, the overall situation in which these creators find themselves is not without precedent.

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, railroads became a driving force in the U.S. economy. Businesses saw goods, services and customers transported with greater ease than at any time before, and massive fortunes were built in the process. But as a handful of large corporations gained outsized power in the space, business owners who centered their products and services exclusively on railroads began to have their fates dictated by forces beyond their control.

History may not repeat itself, but it does rhyme—and in the 21st century, creators operating on non-ownable platforms face a similar situation to their Gilded Age counterparts. While there are plenty of lessons creators can take from that period, three stand out for what they can teach about the perils of over-reliance on non-ownable technology.

1. You can’t fix what you don’t own.

In the era of rail, millions of business owners and entrepreneurs relied on a partnership between the federal government and a handful of major corporations to transport the raw materials, goods and customers that powered their businesses. This system involved cutting-edge technology and required the continentwide coordination of thousands of people. Unfortunately, an error or setback in one part of the system frequently created a cascade effect of delayed arrivals–and when this happened, there was nothing they could do about it.

Meta isn’t a freight train, but in October of 2021, it experienced a problem that was a throwback to the era of the iron horse. Facebook, WhatsApp and Instagram were down for six hours due to a loss of IP routes to Meta’s servers. While no hard figures exist for the amount of money the outage cost creators, Facebook is estimated to have lost $79 million in ad revenue during that period. With a revenue share of advertising accounting for 61% of creator income across all major platforms, the outage sent a financial shockwave throughout the creator class.

Even social media advertising agencies that spend hundreds of thousands a day and global brands like Nike that have a massive presence were left powerless—watching hourly auto-charges pile up on their accounts with little or no recourse for refunds on useless ad spends. Much like their Gilded Age counterparts, when the “train” jumped the tracks, there was nothing creators could do to recoup the loss or prevent it from happening again.

2. You’re in no position to negotiate.

Railway companies could efficiently move goods, set rates for freight, streamline payments for services, and handle the end-to-end details of loading and offloading, which freed up entrepreneurs to spend more time making and selling the best products possible. In the creator economy, a big platform like YouTube offers similar benefits. It gives creators a reach they wouldn’t usually have, has a well-defined process for sharing ad revenue and provides a one-stop shop that enables creators to focus on their craft while delivering steady content flows.

And just like its mighty industrial age predecessors, when the terms and conditions of any of those platforms’ exceptional services change, customers lack the power to negotiate more favorable deals.

Even the top content creators lack the power to negotiate more favorable deals.

New government regulations, algorithm alterations, fickle advertisers, top-down adjustments in take rates—there are extensive potential make-or-break decisions beyond the control of content creators. These non-negotiable factors can pose serious risks for a business, whether it’s a multimillion-dollar brand or a one-person operation. If a creator or brand is over-reliant on a platform’s ability to attract or reach customers, just one unfortunate policy change or regulation could potentially decimate their profits, if not level their company. For example, unilateral changes in copyright use on YouTube can lead to years’ worth of content being demonetized overnight, and possibly to account shutdowns should creators be unable to change tack. Similarly, modifications to take rates on sites like Udemy can potentially cut the incomes of online educators by tens of percentage points within just hours.

While the creator economy revolves around built-in tools and streamlined processes of major platforms, 77% are worried about the fact that they depend on those platforms for earnings. As many as 70% of small creators state that an unfavorable algorithm shift could have seriously reduce their overall income. With the sheer number of creators joining the economy daily, even massive accounts like MrBeast, Yuya and PewDiePie are in no position to negotiate favorable terms should unwelcome, top-down changes be implemented. If they leave, there are thousands of other passengers to take their seats and creators ready to fill the emptied boxcars with content that platforms will push to make up the difference.

While globally recognized brands have the money and resources to fight for better terms, even they can find themselves at the whim of big platforms. Relative to much larger ad spends on traditional media outlets, huge names like Levi’s and PlayStation reach hundreds of millions of eyeballs on the cheap with influencer marketing campaigns. If Dunkin’ is on a multimillion-dollar influencer hot streak with Charli D’Amelio, that’s low-cost and high-return advertising on a key demographic. In the event she forgets to turn off a Spotify playlist in the background of a livestream, however, her channel can get a temporary suspension that knocks it, and the company’s sales, off track for days—even though the company did nothing wrong.

3. The digital world is full of ghost towns.

With the rise of the automobile and air freight, many businesses tied exclusively to rail transit suffered economically. Though some adapted and ultimately thrived, many companies went bust—as did entire towns.

Despite their benefits, in the 21st century, non-ownable platforms pose the same risk to those who rely too heavily on them—and even the relatively short historical record of the creator economy proves this can happen and is likely to happen again. A pioneer of social media that once propelled unknown musicians to global stardom, Myspace now exists as a hollowed-out shell of its former self. While still going strong, Twitter has experienced a tumultuous few years of management changes that have left many uncertain about its future. Despite TikTok’s massive popularity, federal legislators are currently debating curtailing, even outright banning, its use in the United States.

In addition, predicting the arrival of new competitors in the space is impossible. In their early stage, fully immersive virtual communities like the metaverse could lead to the displacement or phasing out of many of today’s leading competitors. Whatever the future alternatives may be, creators could be forced to either uproot their entire operation and move to a new space, or they could be sent back to square one if their business model doesn’t translate—leaving their once-successful business positioned in the right of way of a diminished or shuttered platform.

Brand Central

Given their lack of control over terms, outages and regulations, an increasing number of creators are beginning to stand clear of the big platforms.

Despite the outsized percentage of income that non-ownable platform ad revenue currently accounts for, almost 60% of creators see the future of their businesses relying more on direct earnings from things like product sales, memberships, subscriptions and tips. To transform these income methods into primary revenue streams, more creators are ditching non-ownable platforms to lay the groundwork for an independent infrastructure that is staked out on four principles:

1) Making a personal website brand central

For a generation of smaller creators who have built businesses and reputations on big platforms, the possibility of setting up their own websites—let alone a consideration of the potential advantages of doing so—either hasn’t crossed their minds or, if it has, strikes them as a quaint hobby at best and a dusty relic of Web 1.0 at worst. As many of the world’s most successful brands will testify, however, an owned website is step one in setting yourself up for financial and creative independence.

In terms of time, money and effort, running their own website may have a higher initial cost for a smaller creator. But viewed from the angle of avoiding outages, policy shifts and governmental interventions on big platforms, it’s easy to see how the time and effort of building their own website is an investment worth making.

Controlling the point of access, the means of distribution, and the pricing for their goods and services gives them more freedom with production timetables and content decisions—plus a steadier income. While it’s true that this independence isn’t all encompassing—search engines are still key to the traffic on websites, and creators can’t stop big shifts in how these engines choose what to prioritize—personal websites enable a much greater degree of freedom than platforms. Predicting and creating content that will rank in organic search is much easier to accomplish than ensuring that your content will even be seen on social channels over which creators have no control.

Content creators can’t stop big shifts in how search engines choose what to prioritize.

2) Rerouting from general access to specific experiences

With digital real estate of their own, creators have more control over content and a completely different relationship with the people who consume it. Greater flexibility in how they engage with fans—and how fans engage with one another—allows passive audiences to form into active communities that treat creator websites as go-to destinations for social interactions built around specific interests. While this trend has been visible in the past few years in the form of traditional social media users heading to more niche communities on sites like Reddit and Discord, brands and small creators are beginning to cut out go-betweens altogether.

At present, roughly 20% of creators are earning money via an online community where followers pay to interact not only with them (the creators), but with other community members as well. Almost a quarter are also providing creator-led challenges via their websites for a small fee, giving them a more reliable source of income while also providing the sort of unique, site-centered activity that allows community members to bond over a shared experience.

For smaller creators willing to make the investment, there are also services to help grow these burgeoning communities in an efficient and cost-effective manner. Sites like Paved and SparkLoop allow them to purchase link insertions with popular newsletters for an adjustable fee that meets their budgets. Because newsletter authors tend to carefully select links that align with the content of a particular piece, this helps ensure that advertisements for creator sites are targeted and delivered in an unobtrusive, organic way—and with many sites only charging a fee if click-throughs translate into subscriptions, it guarantees that creators are only paying for advertising that works.

3) Creating a network effect

With engaged communities on personally owned websites, creators can apply the very methods that grew their former platform partners into tech giants. As with TikTok and YouTube, every participant added to a creator’s community isn’t just a new node in their business sphere but a unique individual with their own social connections that can enrich the community experience and draw in those members’ families, friends and acquaintances.

Coming up with new ways to engage members while continuing to produce the high-quality content that brought them to the site in the first place drives up the value of the creator’s work and of the site itself. While all this might seem hypothetical at such an early stage of creator independence, the initial numbers indicate genuine gains. In a 2021 study commissioned by Mighty Networks, 77% of creators who have built self-owned platforms that emphasize user experience stated that they’ve not only increased follower counts and but also grown their revenue.

4) Treating non-ownable platforms as ad space

Running a business on non-ownable platforms can leave a creator at a disadvantage, but treating YouTube, Spotify, Instagram and other big platforms as a cost-free method of advertising to a massive audience provides a substantial upside minus many of the platforms’ key problems. Members of these sites can check out snippets of creator work and, if they want more, can step off the content train and onto a creator’s platform to get it.

Managing a website plus multiple big-platform accounts might sound like an exhausting, potentially unprofitable time sink, but there’s precedent for it being a wise strategy. Using big platforms as limited-access jumping-off points for monetized creator content is an adapted approach of the well-known freemium model. In this model, a creator offers no-charge, pared-down access to content on their website, and then provides premium, full access for a modest fee.

Let’s tweak this slightly to turn non-ownable platforms into the free version and a creator’s website into the paid option. Say you have 30,000 followers on a limited-access Instagram account that does everything it can to entice viewers to jump to your site—where content is more plentiful and of only the best quality. With careful planning and consistent effort, you get 5% of viewers to deboard, walk on over from the station and buy a $5 monthly subscription.

Congratulations! If you’re a smaller creator, you’ve just brought in $7,500 a month without spending a single dollar in advertising or worrying about bans, policy shifts, changes in pay rates or unpredictable advertisers. If you’re a major brand with follower counts in the hundreds of thousands or millions, you’ve dodged the same problems but provided a substantial bump to your quarterly earnings by hitting that conversion rate. Big or small, keeping your community as engaging as possible after drawing in new subscribers or customers gives them an additional reason to stick around, creating a sense of belonging and camaraderie that will do as much for your sales as the quality of your work or products will.

The End of the Line for the Creator Economy

Like the railways of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, many of these platforms are likely to stick around and continue to provide a useful service. While no one knows exactly what that will look like, the history of rail provides yet another indicator of what could happen—and the lessons that those powering the creator economy can take from it.

When rail transport went into decline, many businesses and towns across the country that had hitched their finances to the economic juggernaut collapsed. By and large, the towns and businesses that survived, and in some cases thrived, didn’t do so because they readjusted after the decline, but because they adapted to combat unfavorable conditions while the railroads were still in their ascendency.

When the non-negotiable terms and conditions and technical difficulties of the rails became persistent problems, these individuals and communities strategically uncoupled their fortunes from rail distribution. Fed up, they eliminated dependence while maintaining access—making use of the railroads’ services when needed, but also ensuring that they would never find their businesses reliant on them. Consequently, when rail declined in the coming decades, they didn’t go down with it.

The strategic decision to decrease non-ownable platform reliance is an investment in the economy content creators helped build.

If the history of the railway can provide any guidance, it’s that the current move away from non-ownable platforms doesn’t just present a form of justice in the face of unequal advantages held by the tycoons of content delivery. For creators large and small, the strategic decision to decrease non-ownable platform reliance is an investment in their own brands and in the long-term resilience of the economy they helped build. Because hitching the success of your business to the longevity of a handful of content-delivery engines doesn’t have the best track record.